Covid-19 continues to have multiple impacts along food supply chains, affecting food availability and access, farming and processing, the availability of food workers, cross-border trade, distribution systems, shopping habits and ultimately diets. This range of impacts illustrates a key characteristic of food issues: they are diverse, involving many different groups of people, in different places, engaged in different activities.

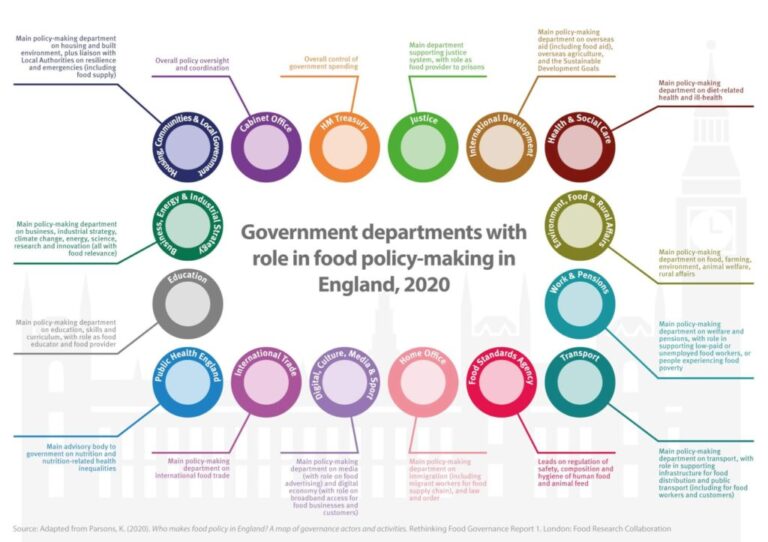

As a consequence, food issues form part of the remit of many different parts of government, from agriculture and health to business and education. Our new Guidance Note[i] on why the government’s response to the Covid-19 food crisis needs to be better coordinated, and the detailed evidence review that underpins it[ii], show that in England, at national level, no fewer than 16 departments are involved in making decisions that affect the food system, with responsibility further subdivided among numerous public bodies. No dedicated department, senior minister or overarching body exists to coordinate food policy.

Policy coordination refers both to the process of connecting the different elements that have input into a policy – such as civil servants, government ministers, departments, agencies, advisory bodies or external stakeholders – and to the process of aligning their goals and plans. Policy coordination is important because without it:

- Confusion can arise over what the government’s policy is;

- Policies can undermine each other or pull in opposite directions;

- Policies can duplicate each other;

- There can be missed opportunities for double benefits;

- Along with the desired outcomes, policies can have undesirable unforeseen consequences;

- Issues can fall through the cracks because departments or officials think someone else is responsible.

The Covid-19 pandemic is an exceptional event, and it would have been unreasonable to expect any government to be fully prepared for its effects. But it quickly became clear that better coordination among relevant parts of government would have strengthened the response in the short term. For example, it could have helped match supply and demand when restaurants and hotels were ordered to close, leaving huge volumes of food destined for the catering sector stranded, just at the time when supermarket shelves were being emptied and many people found themselves without an income and unable to buy sufficient food. And it could have avoided the anxiety that ensued when schools closed and children in receipt of Free School Meals were left without a vital source of nourishment.

At local level, voluntary organisations and businesses have jumped into action to plug the gaps, doing an admirable job of getting food to people who need it, and thereby keeping businesses trading and preventing waste. What is missing is a coordinated response from central government.

Among other things, this could ensure that:

- Sufficient quantities of nutritious food are made available to consumers on a fair basis;

- The multiple organisations currently coordinating efforts to match supply and demand at community level have the clarity and guidance they need;

- The UK’s small-scale food businesses (many of which are financially precarious at the best

- of times), and the infrastructure they depend on, survive into the future;

- Government retains credibility as guardian of the nation’s nutritional health and wellbeing.

From time to time, coordinating bodies have been set up to allow relevant expertise to be brought together from across government and from external sources, to focus on specific policy problems or take a broad view of food policy. One current example is the Childhood Obesity Plan, which is led by the Department of Health and Social Care but involves action by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and the Department for Education, as well as by the food industry.

Never in recent British history has it been more evident that a coordinated approach to food policy is needed. A cross-government committee on the food system would be a starting point, to connect policy during the crisis and continue into the renewal process and beyond. In the short term, better policy coordination will boost the effectiveness of the government’s response and rebuild trust. In the longer term, it could lay the foundation for a more resilient food system, meeting goals on health, fairness, environmental sustainability and economic diversity – and better able to withstand shocks like the current one.

[i] Rosalind Sharpe, Kelly Parsons and Corinna Hawkes (2020) Coordination must be key to how governments respond to Covid-19 food impacts: a view from England. Rethinking Food Governance Guidance Note. London: Food Research Collaboration.

[ii] Kelly Parsons (2020). Who makes food policy in England? A map of government actors and activities. Rethinking Food Governance Report 1 London: Food Research Collaboration

Both reports are available at: https://foodresearch.org.uk/publications/who-makes-food-policy-in-england-and-food-policy-coordination-under-covid19/